Despite working in an industry where he was surrounded by well qualified graduates, he himself got by with three fake degrees purchased from the fictional Middleham University (Leeds). Of course, I'd spotted the forgeries because I know that Middleham is a small market town in North Yorkshire with a fine tradition of training race horses, a wonderful old castle but nothing at all corresponding to a University.

But by talking to him you could tell that he wasn't at all embarrassed by his relative lack of formal education and that he regarded the rest of us as fools for not working out that it was just the piece of paper that mattered (and why waste potential money making time studying when you could just buy one off the shelf). In Trumpian terms he was the winner and we, by definition, were losers.

Like Trump, his only interest in other people was in what they could do for him and, like Trump, there was a huge turnover of workers as people worked out what was going on and fell from favour. Like Trump, he covered up his lack of real knowledge with anecdotal bluster. If anyone had ever tried to get him to explain the concept of energy, or distinguish a kW from a kWh, I've no doubt that he would have done what he always did and gone off an extended personal anecdote. An anecdote designed not only to cover up his lack of real knowledge, and take up the time where this lack might be exposed, but also to big up his own prior "achievements".

At one stage a glossy brochure was produced to promote the company. A full page spread showed a picture of him with the quote "Doing nothing is not an option" he couldn't help but put his own name to it. Just like Donald Trump he had an obsession with self promotion.

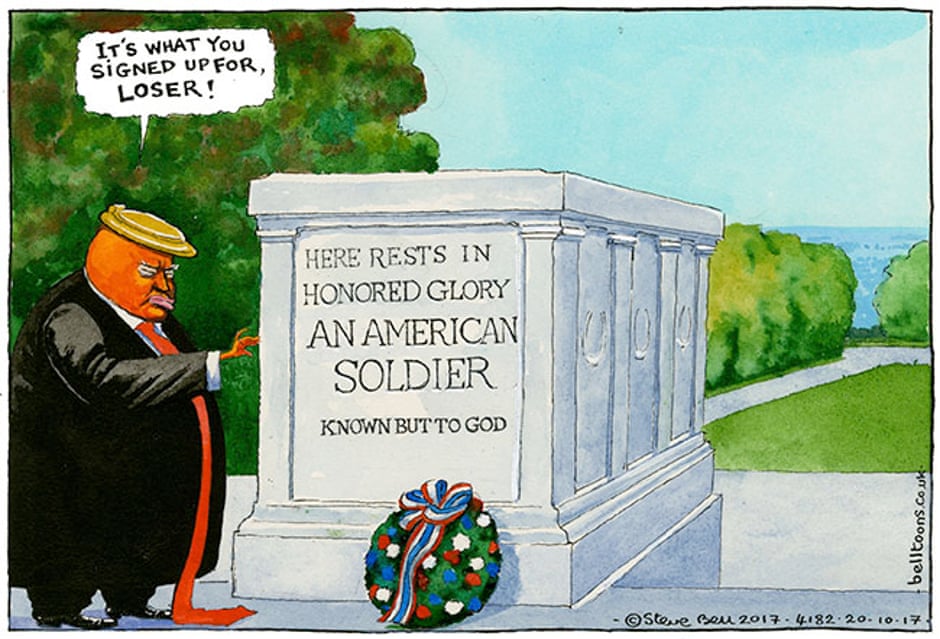

So, when Donald Trump says "Nobody knew health care could be so complicated" it's because he couldn't bring himself to say "I never knew health care was so complicated". To do so would have admitted his own ignorance. When he tells the family of a dead American soldier that "He knew what he was getting into" it's the Donald's way of reminding himself, and the rest of us, that he was too smart to get drafted.

Finally, like Trump, he was a sexual predator. Indeed, when I did expose him to the relevant authorities (in his case the UNFCCC), the thing that made me jump rather sooner than I probably should have done were the tales told to me, in confidence, about how he'd harassed women in the company.

This is an account of our last days working together. He still owns the company but it's now base in India not South Africa.

Cartoon with thanks to Steve Bell (The Guardian 20/10/2017)